Every little increase in human freedom has been fought over ferociously between those who want us to know more and be wiser and stronger, and those who want us to obey and be humble and submit. - Philip Pullman

Yuval Noah Harari’s books are some of my favourite books of all time - they are writen in a very accessible but incredibly logical way and managed to blow my mind multiple times with Harari’s outstanding big-picture thinking. I love both Homo Deus and Nexus and am right now reading Sapiens, but in this short essay I wish to specifically address the problems presented in the book Nexus, which humanity will have to solve in the near future.

Nexus addresses the structure of human information networks throughout history, how they evolved, how they enabled democracy but also totalitarian dictatorships and how they will likely change due to the rise of digital networks, automation (bots), large language models (LLMs) and generative artificial intelligence (AI). It also addresses the many dangers posed by non-human intelligence (in our case AI) in modern democratic discussions. Harari proposes that social media platforms ban bots for example.

In this informal essay I also wish to stress the need for more privacy as well as present a new solution for solving the current Social Network Algorithm Problem (SNAP) - the Positive Reinforcement Algorithm (PRA).

Introduction#

Fundamentally, human societies are based on fictional realities (such as rules, laws, customs and even ethics), which don’t exist in the real physical world. This ability to create fictional realities, which many people belive in has enabled humans to establish modern civilisation unlike any other animal. Harari argues that if you simply tell the unvarnished truth, no one will pay attention. Consequently, you would have no power, as power comes from the stories you convince other people to believe. There will never be a society that values truth over power. Nevertheless, he insists that facts do exist, separate from myths and propaganda. Scientists and journalists need to do their best to spin stories around facts rather than derive “facts” from stories. Some stories are able to create a third level of reality: intersubjective reality. Whereas subjective things like pain exist in a single mind, intersubjective things like laws, gods, nations, corporations, and currencies exist in the nexus between large numbers of minds. More specifically, they exist in the stories people tell one another. The information humans exchange about intersubjective things doesn’t represent anything that had already existed prior to the exchange of information; rather, the exchange of information creates these things.

The book Nexus presents two different views on information - the naive and the populist view. The core tenet of the naive view of information is that information is an essentially good thing, and the more we have of it, the better. Given enough information and enough time, we are bound to discover the truth about things ranging from viral infections to racist biases. This naive view justifies the pursuit of ever more powerful information technologies and has been the semiofficial ideology of the computer age and the internet. Populists are suspicious of the naive view of information and claim that information is only a tool for power and thus cannot be trusted except for their wise leader, who seeks to overthrow the corrupt elites. Populists are eroding trust in institutions like universities, journalism and international cooperation just when humanity faces existential challenges of ecological collapse, global war, and out-of-control technology.

Information isn’t the raw material of truth, but it isn’t a mere weapon, either. There is enough space between these extremes for a more nuanced and hopeful view of human information networks and of our ability to handle power wisely.

Features of democratic and authoritarian information networks#

Firstly it’s important to understand that in a democracy, there are:

- Plentiful and decentralised sources of information (for example several news sources, various authors, bloggers etc.)

- Strong fact-checking and corrective mechanisms (when falsehoods are spread by one informational source they are called out by another source)

- Debate (Various paradigms and narratives are evaluated using reason)

These properties enable democracies to constantly evolve - if a democratic society makes a mistake, it can be corrected. This has made democratic societies the most flexible and resilient societies in human history. Democratic information networks work in a similar fashion to the scientific method - our rules and ethics are like a paradigm, they are assumed to be optimal given our collective knowledge, and if a better paradigm gets found, it gradually replaces the old one. Democracies are essentially utilitarian - they seek to maximise happiness and well-being of as many people in the population as possible in the long run.

In authoritarian information networks however we see the following properties:

- Centralised and limited information sources

- Surpression and censorship of dissenting narratives

One merely needs to think about dictatorships like Nazi-Germany, the USSR or modern day countries like Iran, Putin’s Russia or China.

AI, democracy and privacy#

In the past total surveillance of people was simply practically impossible. It was not possible to watch every person all the time, because there just weren’t enough officers and data processing centres to facilitate such a police state - even in the USSR during the Stalin era, the NKVD couldn’t surveil the whole population 24/7 - simply because the number of agents was limited.

With machine learning, AI increased storage and data processing capabilities, the surveillance state of the 21st century really can observe the entire population 24/7.

Governments and corporations are now using the latest technologies to keep track of us online and offline. From Facial recongition systems and biometric passport data to online data tracking - these technologies can leave a signifcant information trail. This trail can be used to solve crimes, but also opens the doors to totalitarian nightmares. In places like Iran, for example, facial recognition is used to enforce dress codes, leading to severe privacy invasions and punishments.

With AI, it might become truly impossible to resist a totalitarian dictatorship, as it would recognise dissent in its roots and can attend to every individual dissident individually. Resistance requires dissidents to connect, but this is impossible, if an all-knowing program were to isolate every Andersdenker.

Humans don’t have free will and our patterns are highly predictable, though not fully deterministic. Algorithms can even find out things about us that we didn’t know ourselves, such as the sexuality of people.

Even in a democracy, if people’s privacy isn’t protected, political parties, foreign actors (such as Russia, I can really recommend this article by the Süddeutsche Zeitung or Mueller’s Report on the 2016 Russian interference in the 2016 US election) and especially corporations (especially big tech) can dramatically influence the outcome of the election by personalising propaganda of political parties that further their interests. This way special interest groups do not only get more attention from users of the internet, but can also adapt AI-based bots to change the opinions of the users, based on the information about the user. Whoever controls the most AI bots, controls the narrative:

Equally alarmingly, we might increasingly find ourselves conducting lengthy online discussions about the Bible, about QAnon, about witches, about abortion, or about climate change with entities that we think are humans but are actually computers. This could make democracy untenable. Democracy is a conversation, and conversations rely on language. By hacking language, computers could make it extremely difficult for large numbers of humans to conduct a meaningful public conversation. When we engage in a political debate with a computer impersonating a human, we lose twice. First, it is pointless for us to waste time in trying to change the opinions of a propaganda bot, which is just not open to persuasion. Second, the more we talk with the computer, the more we disclose about ourselves, thereby making it easier for the bot to hone its arguments and sway our views. In the 2010s social media was a battleground for controlling human attention. In the 2020s the battle is likely to shift from attention to intimacy. One analysis estimated that out of a sample of 20 million tweets generated during the 2016 U.S. election campaign, 3.8 million tweets (almost 20 percent) were generated by bots. By the early 2020s, things got worse. A 2020 study assessed that bots were producing 43.2 percent of tweets. A more comprehensive 2022 study by the digital intelligence agency Similarweb found that 5 percent of Twitter users were probably bots, but they generated “between 20.8% and 29.2% of the content posted to Twitter.” Now a political party, or even a foreign government, could deploy an army of bots that build friendships with millions of citizens and then use that intimacy to influence their worldview.

Privacy is not only essential to protect humanity from the totalitarian potential of nonhuman intelligence, but also to provide the members of a democracy with sufficient intimacy from opinion-altering AI to make independent decisions.

Epistemological danger#

I would like to touch on the epistemology of AI. In Iran facial recognition algorithms are now being used to identify women who do not wish to adhere to the stringent dress codes present in the islamic theocracy - these women would then be sent to psychiatric help by the automated Iranian surveillance state. In a truly Black Mirror fashion these women actually first receive warning SMSs followed by detention.

But wait if an aritifical intelligence says that Black people are inherently more likely to cause crime thus to prevent crime they should be ostracised, that Women should be denied their rights to dress as they want because there is an all-knowing god who wills so, or that Jews are inherently evil and thus need to be exterminated, does this mean that the AI is right? After all isn’t the AI supposed to make objective decisions?

The answer is a clear no, the output and/or decisions of the AI are inherently shaped by the training data. The weights in the Neural Network are trained on real life data sets (in the case of LLMs texts) and their knowledge is purely delimited to the knowledge present in the training set. However the training set can easily contain falsehoods, cultural norms, religion as well as prejudice and hatred. Just imagine training a chat bot on 4chan posts.

Logical reasoning as it was introduced in the most recent large language models (such as o1 - which mimic the slow reasoning present in human brains as described by the psychologist Daniel Kahneman), sadly doesn’t fix this issue. Logics can only be applied within the scope of mathematics and scientific problems. Except for mathematics, logic doesn’t tell us much about the world we live in with the sole exception of the fact that we must exist, because we think (as established by Rene Descartes). From logic alone we cannot derive ethics and we cannot even derive facts about our world - such as if evolution is real or if we live in a simulation. In the case of evolution, it is empirical data that confirms a hypothesis (the theory must however make logical sense, but its confirmation is dependent on what we observe in the real world). Even physics is fundamentally built on empirical observations. The universe is not inherently deontological or utilitarian, there is no natural property which implies that levying interests is a sin. So if an AI uses logical reasoning to make an informed decision based on (for example) perfectly logical utilitarian reasoning, this reasoning is not objective - it was the human that made the AI use utilitarian logic. Likewise it is the human which passes all the prejudices and falsehoods on to the AI. A society controlled by AI is not an objectively moral or optimal society.

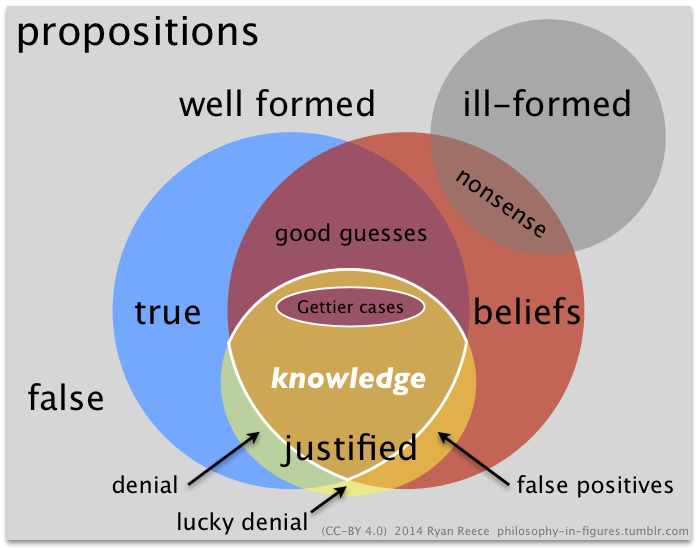

In terms of this diagram, AI is trained on beliefs which also contain nonsense, false positives and denials. But given the effectiveness with which AI can control a society or spread the propaganda, AI could mean the resurgence of religion and spirituality.

With that I wish to go to the main point of this short essay.

The Social Network Algorithm Problem (SNAP)#

I would like to being this chapter with the following video:

Technology Connections correctly identifies that nowadays algorithms are responsible for the content we see and people, especially in the realm of social media, are barely in control of the posts, videos and content they see (which used to be achieved by following and subscribing in the past) - he termed this phenomenon as algorithmic complacency, where people completely give up the control over the content they see to the recommendation algorithm of a certain platform.

Recommendations can have signifcant impact on the opinions of people. The for example Bible was born as a recommendation list by a council of priests. By taking the misogynist 1 Timothy instead of the more egalitarian Acts of Paul and Thecla when the Bible was compiled, Athanasius and other priests changed the course of history. In the case of the Bible, ultimate power lay not with the authors who composed different religious documents but with the curators who made a selection among the religious documents and turned them into compiled books like the Vedas, Torah, Bible or the Quran. This was the power wielded in the 2010s by social media algorithms.

This brings me to the most important excerpt from the book Nexus:

In 2016–17 a small Islamist organization known as the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) carried out a spate of attacks aimed to establish a separatist Muslim state in Rakhine, killing and abducting dozens of non-Muslim civilians as well as assaulting several army outposts. In response, the Myanmar army and Buddhist extremists launched a full-scale ethnic-cleansing campaign aimed against the entire Rohingya community. They destroyed hundreds of Rohingya villages, killed between 7,000 and 25,000 unarmed civilians, raped or sexually abused between 18,000 and 60,000 women and men, and brutally expelled about 730,000 Rohingya from the country. The violence was fueled by intense hatred toward all Rohingya. The hatred, in turn, was fomented by anti-Rohingya propaganda, much of it spreading on Facebook, which was by 2016 the main source of news for millions and the most important platform for political mobilization in Myanmar.

An aid worker called Michael who lived in Myanmar in 2017 described a typical Facebook news feed: “The vitriol against the Rohingya was unbelievable online—the amount of it, the violence of it. It was overwhelming…. [T]hat’s all that was on people’s news feed in Myanmar at the time. It reinforced the idea that these people were all terrorists not deserving of rights.” In addition to reports of actual ARSA atrocities, Facebook accounts were inundated with fake news about imagined atrocities and planned terrorist attacks. Populist conspiracy theories alleged that most Rohingya were not really part of the people of Myanmar, but recent immigrants from Bangladesh, flooding into the country to spearhead an anti-Buddhist jihad. Buddhists, who in reality constituted close to 90 percent of the population, feared that they were about to be replaced or become a minority.

Without this propaganda, there was little reason why a limited number of attacks by the ragtag ARSA should be answered by an all-out drive against the entire Rohingya community. And Facebook algorithms played an important role in the propaganda campaign. While the inflammatory anti-Rohingya messages were created by flesh-and-blood extremists like the Buddhist monk Wirathu, it was Facebook’s algorithms that decided which posts to promote. Amnesty International found that “algorithms proactively amplified and promoted content on the Facebook platform which incited violence, hatred, and discrimination against the Rohingya.” A UN fact-finding mission concluded in 2018 that by disseminating hate-filled content, Facebook had played a “determining role” in the ethnic-cleansing campaign.

Readers may wonder if it is justified to place so much blame on Facebook’s algorithms, and more generally on the novel technology of social media. If Heinrich Kramer used printing presses to spread hate speech, that was not the fault of Gutenberg and the presses, right? If in 1994 Rwandan extremists used radio to call on people to massacre Tutsis, was it reasonable to blame the technology of radio? Similarly, if in 2016–17 Buddhist extremists chose to use their Facebook accounts to disseminate hate against the Rohingya, why should we fault the platform? Facebook itself relied on this rationale to deflect criticism. It publicly acknowledged only that in 2016–17 “we weren’t doing enough to help prevent our platform from being used to foment division and incite offline violence.” While this statement may sound like an admission of guilt, in effect it shifts most of the responsibility for the spread of hate speech to the platform’s users and implies that Facebook’s sin was at most one of omission—failing to effectively moderate the content users produced. This, however, ignores the problematic acts committed by Facebook’s own algorithms.

The crucial thing to grasp is that social media algorithms are fundamentally different from printing presses and radio sets. In 2016–17, Facebook’s algorithms were making active and fateful decisions by themselves. They were more akin to newspaper editors than to printing presses. It was Facebook’s algorithms that recommended Wirathu’s hate-filled posts, over and over again, to hundreds of thousands of Burmese. There were other voices in Myanmar at the time, vying for attention. Following the end of military rule in 2011, numerous political and social movements sprang up in Myanmar, many holding moderate views. For example, during a flare-up of ethnic violence in the town of Meiktila, the Buddhist abbot Sayadaw U Vithuddha gave refuge to more than eight hundred Muslims in his monastery. When rioters surrounded the monastery and demanded he turn the Muslims over, the abbot reminded the mob of Buddhist teachings on compassion. In a later interview he recounted, “I told them that if they were going to take these Muslims, then they’d have to kill me as well.”

In the online battle for attention between people like Sayadaw U Vithuddha and people like Wirathu, the algorithms were the kingmakers. They chose what to place at the top of the users’ news feed, which content to promote, and which Facebook groups to recommend users to join. The algorithms could have chosen to recommend sermons on compassion or cooking classes, but they decided to spread hate-filled conspiracy theories. Recommendations from on high can have enormous sway over people. Sometimes the algorithms went beyond mere recommendation. As late as 2020, even after Wirathu’s role in instigating the ethnic-cleansing campaign was globally condemned, Facebook algorithms not only were continuing to recommend his messages but were auto-playing his videos. Users in Myanmar would choose to see a certain video, perhaps containing moderate and benign messages unrelated to Wirathu, but the moment that first video ended, the Facebook algorithm immediately began auto-playing a hate-filled Wirathu video, in order to keep users glued to the screen. In the case of one such Wirathu video, internal research at Facebook estimated that 70 percent of the video’s views came from such auto-playing algorithms. The same research estimated that, altogether, 53 percent of all videos watched in Myanmar were being auto-played for users by algorithms. In other words, people weren’t choosing what to see. The algorithms were choosing for them.

But why did the algorithms decide to promote outrage rather than compassion? Even Facebook’s harshest critics don’t claim that Facebook’s human managers wanted to instigate mass murder. The executives in California harbored no ill will toward the Rohingya and, in fact, barely knew they existed. The truth is more complicated, and potentially more alarming. In 2016–17, Facebook’s business model relied on maximizing user engagement in order to collect more data, sell more advertisements, and capture a larger share of the information market. In addition, increases in user engagement impressed investors, thereby driving up the price of Facebook’s stock. The more time people spent on the platform, the richer Facebook became. In line with this business model, human managers provided the company’s algorithms with a single overriding goal: increase user engagement. The algorithms then discovered by trial and error that outrage generated engagement. Humans are more likely to be engaged by a hate-filled conspiracy theory than by a sermon on compassion or a cooking lesson. So in pursuit of user engagement, the algorithms made the fateful decision to spread outrage.

Events in Myanmar in the late 2010s demonstrated how decisions made by nonhuman intelligence are already capable of shaping major historical events. We are in danger of losing control of our future. A completely new kind of information network is emerging, controlled by the decisions and goals of an alien intelligence. At present, we still play a central role in this network. But we may gradually be pushed to the sidelines, and ultimately it might even be possible for the network to operate without us. Some people may object that my above analogy between machine-learning algorithms and human soldiers exposes the weakest link in my argument. Allegedly, I and others like me anthropomorphize computers and imagine that they are conscious beings that have thoughts and feelings. In truth, however, computers are dumb machines that don’t think or feel anything, and therefore cannot make any decisions or create any ideas on their own.

This objection assumes that making decisions and creating ideas are predicated on having consciousness. Yet this is a fundamental misunderstanding that results from a much more widespread confusion between intelligence and consciousness. I have discussed this subject in previous books, but a short recap is unavoidable. People often confuse intelligence with consciousness, and many consequently jump to the conclusion that nonconscious entities cannot be intelligent. But intelligence and consciousness are very different. Intelligence is the ability to attain goals, such as maximizing user engagement on a social media platform. Consciousness is the ability to experience subjective feelings like pain, pleasure, love, and hate. In humans and other mammals, intelligence often goes hand in hand with consciousness. Facebook executives and engineers rely on their feelings in order to make decisions, solve problems, and attain their goals.

But it is wrong to extrapolate from humans and mammals to all possible entities. Bacteria and plants apparently lack any consciousness, yet they too display intelligence. They gather information from their environment, make complex choices, and pursue ingenious strategies to obtain food, reproduce, cooperate with other organisms, and evade predators and parasites. Even humans make intelligent decisions without any awareness of them; 99 percent of the processes in our body, from respiration to digestion, happen without any conscious decision making. Our brains decide to produce more adrenaline or dopamine, and while we may be aware of the result of that decision, we do not make it consciously.

The process of radicalization started when corporations tasked their algorithms with increasing user engagement, not only in Myanmar, but throughout the world. For example, in 2012 users were watching about 100 million hours of videos every day on YouTube. That was not enough for company executives, who set their algorithms an ambitious goal: 1 billion hours a day by 2016. Through trial-and-error experiments on millions of people, the YouTube algorithms discovered the same pattern that Facebook algorithms also learned: outrage drives engagement up, while moderation tends not to. Accordingly, the YouTube algorithms began recommending outrageous conspiracy theories to millions of viewers while ignoring more moderate content. By 2016, users were indeed watching 1 billion hours every day on YouTube.

YouTubers who were particularly intent on gaining attention noticed that when they posted an outrageous video full of lies, the algorithm rewarded them by recommending the video to numerous users and increasing the YouTubers’ popularity and income. In contrast, when they dialed down the outrage and stuck to the truth, the algorithm tended to ignore them. Within a few months of such reinforcement learning, the algorithm turned many YouTubers into trolls.

The social and political consequences were far-reaching. For example, as the journalist Max Fisher documented in his 2022 book, The Chaos Machine, YouTube algorithms became an important engine for the rise of the Brazilian far right and for turning Jair Bolsonaro from a fringe figure into Brazil’s president. While there were other factors contributing to that political upheaval, it is notable that many of Bolsonaro’s chief supporters and aides had originally been YouTubers who rose to fame and power by algorithmic grace.

Pictures of the storming of the US and Brazilian congresses

As the excerpt showcases the problem with modern social media is that recommendation algorithms, these are the algorithms that show users recommended content and are usually seperate from their subscription and friend recommendations, are:

- actively encouraging outrage, division and disinformation

- being manipulated by increasingly sofisticated bots for political or corporate gain

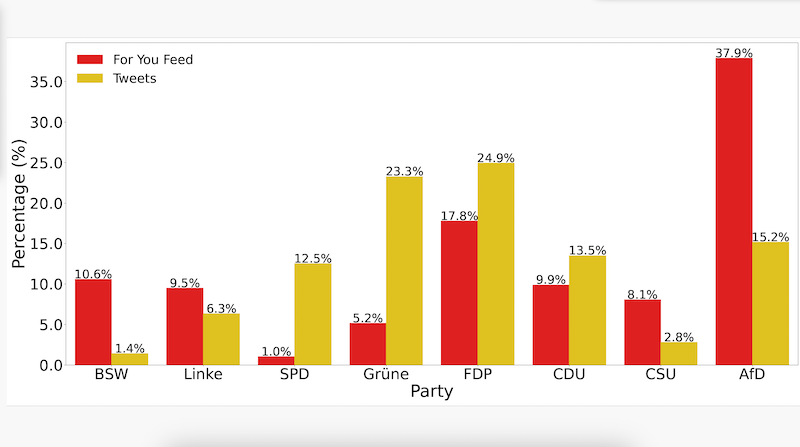

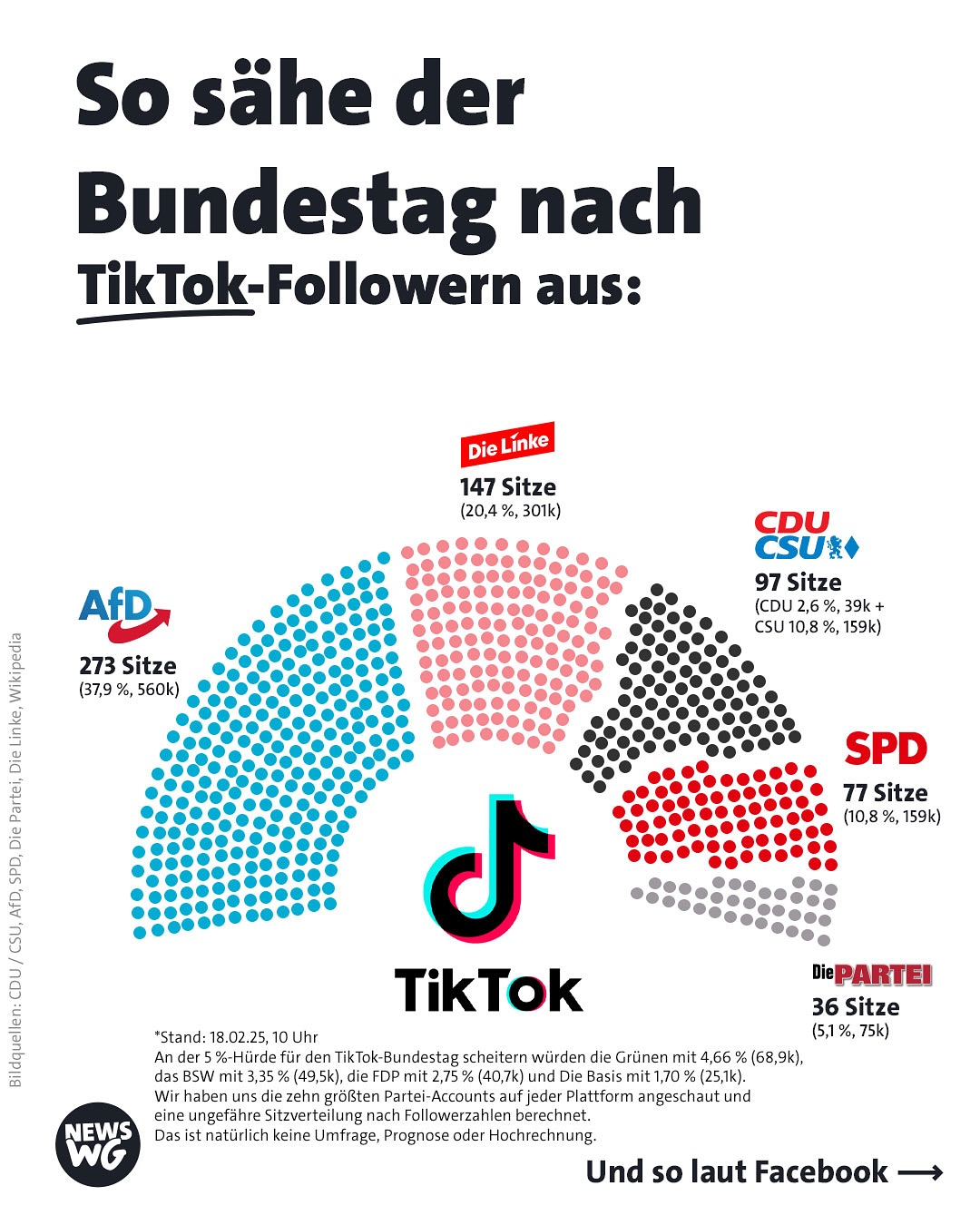

Before the 2025 German Federal Election the following interesting patterns could be observed:

It is very clear that many platforms, especially TikTok and X, formerly known as Twitter, massively distort the attention in political debate thus boosting fringe parties and preventing constructive democratic dialogue which is necessary for a functioning democracy.

The graph above shows that older people were the least likely in Germany to vote for the AfD and BSW. This very likely indicates that social media is indeed responsible for the rise in populist parties and for the weakening of non-populist parties, because:

- older people are generally more conservative (and thus the AfD/BSW share should’ve been higher among older people)

- older people are generally not as technically skilled and have had the least contact with social media

The Social Media Algorithm Problem (SNAP) is thus the phenomenon, where recommendation algorithms of major platforms manipulate the attention economy and facilitate the spread of outrage, division, disinformation and other negative phenomena such as religious radicalisation (most islamist terrorist attacks in Europe are the result of radicalisation on social media, which encourage the spread of hateful and radical ideologies). These recommendation algorithms are a form of a negative feedback algorithm; the more attention people give to outrage and disinformation, the more the algorithm pushes outrage (mainly for profit reasons) - with a destabilising effect for democracies worldwide - from Washington to Wellington and from Brasilia to New Delhi, democracies are being put to a test, as jerks receive all the attention - but the reality is that democracy cannot base itself on cynicism lead by jerks, who constantly wish to tear down any system in place. Democracy requires reforms not revolutions, expertise not hobby contrarians and compromise not constant division - a society where people can’t even agree on basics facts and vilify each other are a recipe for dictatorship.

Democracy requires self-correction mechanisms - the distribution of power, a strong judiciary, a strong opposition, decentralisation of information sources and fact-checking of one’s own sources and of others; to be a credible news source factchecking was instrumental, it was necessary to be seen professional. SNAP however changed the dynamic, credible sources simply cannot compete against non-professional sources such as social media influencers. Their coverage has a sway over a lot of people - a significant portion of the population only comes in contact with the news through social media - however SNAP has made sure that the spread of information in now facilitated completely by unprofessionals and is as riddled with false information, outrage and divisive commentary. Additionally it accelerates the sway of public opinion by means of saturating posts made by bots that push for a certain narrative - thus artificially getting more attention of the users and thus having a greater probability of swaying their perception of or opinion on a topic or at least make the user ambivalent. A lie told often enough becomes the truth.

In the past people who lied and spread false information would be grilled on their falsehoods on TV and almost all the screentime they would get would be on their false statements undermining their credibility, but with social media networks and SNAP fact-checking content cannot keep up with the much simpler and more appealing disinformation, especially if backed by an army of bots. Exactly for this reason the removal of fact checkers from Meta is so dangerous - it would exacerbate SNAP and allow bots to spread disinformation without any checks and balances. In a SNAP system fact-checking cannot compete with disinformation. Eroding the consensus on even the most basic facts and institutions lays ground for “a world that’s right for a dictator” as the Nobel peace prize winner Maria Ressa puts it.

Additionally Elon Musk’s comments that “legacy media” (non-social media news organisations such as the BBC or newspapers like die Zeit, the Guardian, Le Monde or the New York Times) are obsolete because of social media platforms is a very dangerous sentiment, because of two reasons:

- Reading news from social media is full of misinformation and disinformation (note that misinformation is false information spread without the intent to mislead, while disinformation is false information that is deliberately spread to deceive others), opinions and emotions. Yes there is a time delay between a breaking news being posted in real time on Facebook and an article appearing on the BBC website, but you can be much more certain about about the accuracy on the BBC than on Facebook - a notable example is how Storm-1516 spread fabricated videos of ballot shredding in Leipzig, but these turned out to be false and fabricated. If we base our perception exclusively on real-time news, we surrender ourselves to manipulation. The truth is worth the time delay. As AI progresses it will be harder to differentiate between real and fake videos, which exactly why we need professional journalists to process information for us reliably.

- Social media websites are effectively a news-outlet of their own and centralising information sources on one platform is a very dangerous precedent, because democracy requires decentralisation. While users making posts is decentralised, the recommendation algorithm that determins what users get to see is not and is effectively equivalent to an editor in a newspaper. Yes news outlets are often opinionated (my favourite newspaper The Guardian is a good example of that), but that’s why one should never only read one source. If democratic society obtains its news from only a few social media networks, these gain unprecedented power over our society. Social media networks and established newsoutlets are not mutually exclusive and can work together.

The attention economy can be manipulated extremely well through bots - the best example of this is the Russian disinformation campaign after the invasion of Ukraine. Liberal democracies and their societies were unanimous in condemning the Russian aggression and war of conquest. But as time went on the Kremlin narrative and/or ambivalence became increasingly widespread. This shouldn’t be surprising as Kremlin bots artificially saturated the discussion and took advantage of SNAP. This campaign was very successful, especially on the political fringes (both left and right) and even got into government in countries like the US and Slovakia. If yet another democracy gets attacked by a dictatorship in the future, will other democracies allow the dictatorships to divide and conquer them?

Proposal#

Harari’s bot ban#

Harari makes a bold proposal to improve sthe digital democratic discourse - a ban on bots. It’s a fairly simple solution that would remove the possibility of internal and external special interest groups from manipulating the political debate of a country and I completely agree. Banning bots is not a restriction on freedom of speech, because bots are not humans and don’t have any rights. I think it’s also a good idea to separate content that was completely human-made and that made with siginificant contributions of AI, because social media should first and foremost be about connecting people and human interaction. Here’s a practical analogy: We right now have very advanced computer chess playing models and they are all better than humans, and yet we humans still play chess. But playing chess with a computer is quite boring as people prefer to play with real humans and using bots to cheat is not allowed (we have embraced bots for analysis though and they are great at that). Why not pursue the same strategy with social media? A ban on bots would be the most significant step towards protecting democracies from foreign actors and it prevent a Hararian dystopia, where social media becomes dominated by AI bots whose sole purpose is to intimately know you and convince you that freedom and democracy are bad. Would you want to be active on a social media platform where the majority of users and posts are made by computers?

However while I think a bot ban would be the first major step in the right direction, it wouldn’t fix the fundamental SNAP problem that social media has had before the rise of high-performance LLMs. The Rohingya genocide didn’t happen because a foreign power or company intentionally flooded Facebook with bots that spread hatred, it happened because the recommendation algorithms specifically spread hatred and outrage maximising content (with the simple desire to maximise screen time and thus ad revenue), giving an unproportional and unfair advantage when recommending content to hatred and outrage. Political polarisation is rising across the world, but even if we ban bots and the majority posts only polite and mutually respectful posts, the divisive ones will always be favoured by SNAP (negative reinforcement algortihms) - thus continuing the vicious cycle of polarisation.

Positive Reinforcement Algorithms#

Positive Reinforcement Algorithms, PRA or positive Rückkopplungsalgorithmen in German are the second step in solving SNAP, these recommendation algorithms aim to maximise user engagement and to offer the users accurate personalised results, but PRAs intentionally downrank political and historical content containing disinformation, outrage, and division. Note that PRA does no censoring, freedom of speech is integral to democracy and outrage posts are an integral part of the internet, but it does rank non-divisive, credible and calm posts higher than their counterparts. Users can and are encouraged to read the posts of other users and communities that they subscribed to, but manually. PRAs encourage quality instead of ragebaiting and if applied ambitiously could also solve other problems stemming from social media such as bodyshaming, inadequacy-stemming depression (this can be achieved by using the Pareto principle to also show posts of people having issues in order to relate with them), doomscrolling, fear of missing out, religious radicalisation as well as encourage creativity and optimism. PRAs are intrisically conservative in the sense that they seek to reform social media to increase trust in the democratic process, return back to the more pristine state of the early days of social media and return to a level of content professionalism present in television.

A central assumption by PRA is that every post can be vectorised into various categories such as topic, user engagebility (which can be obtained with test samples), including the outrage-factor etc. This can be easily achieved nowadays with LLMs and DL Models - especially high speed LLMs such as Mistral Small 3 by Mistral AI.

It is extremely important that PRAs are politically neutral. PRA must not discriminate against any political opinion, no matter if left-wing, centrist or right-wing - about taxing the rich or restricting immigration - as this could lead to catastrophic results for democracy, where the algorithm actively silents new ideas and criticism of an existing narrative. This could be especially problematic if a PRA reinforces the narrative of an authoritarian government - this would be yet another Hararian dystopia, where non-human intelligence controls a democracy. PRAs exist purely to improve the nature of discussion, not its content.

But isn’t PRA then a form of censorship that purpusefully gives more attention to some users? The answer is no, platforms such as Youtube, Facebook, X and Reddit need to constantly make a selection of which content among a huge pool of posts and videos to show the user - everyone can find the video or post of every user, but not every video or post is recommended in the feed. Are big platforms then favouring arseholes and censoring non-arseholes? One could argue that the only fair selection would be to recommend random posts or videos from a given time window, but I disagree as this can be manipulated as well - one merely needs to saturate the total pool of content with their posts thus controlling even a random recommendation algorithm. We need to accept the fact that there is no single objectively fair recommendation algorithm and that we need to rationally decide on how to best perform the selection. Thus there also needs to be transparency about how the PRA works and how it was trained, the details of the recommendation algorithm itself however need not be open-sourced, as to prevent abuse.

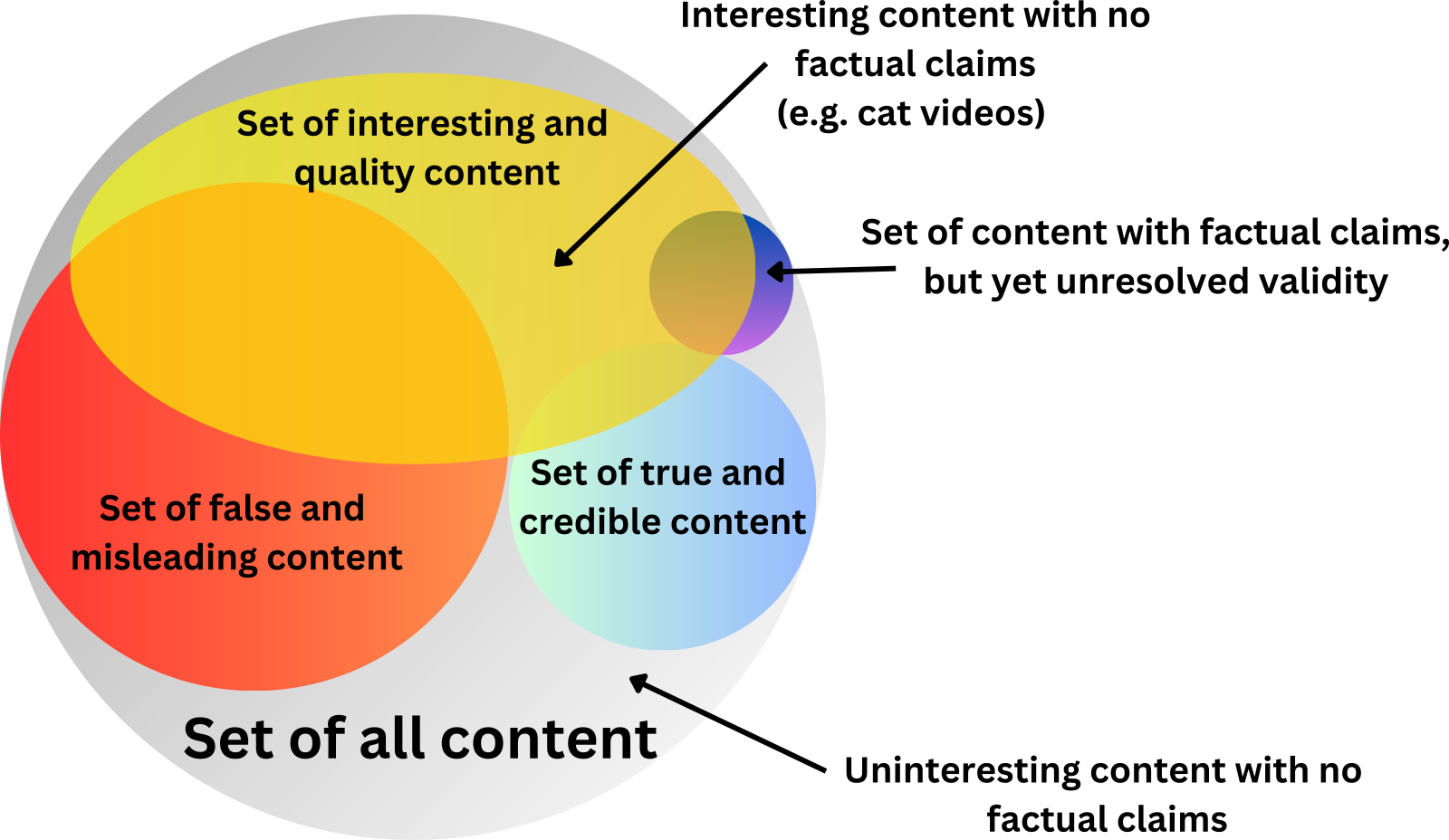

It’s important to visualise the Venn’s diagramms on the type of content found on social media:

- Some content is interesting or has high quality (this kind of content is typically recommended)

- Some content makes factual statements (some a true, some are false, some misleading, some have credible sources, while others don’t - and then there is also the set of content with factual claims but yet unresolved validity - the best example of this includes the latest studies, real-time news and leaks)

PRAs just like most recommendation algorithms rank interesting and/or quality content highest, however they specifically downrank political and historical content that contains misinformation or disinformation (in terms of the practical application Wikipedia can be used as a reliable source), outrage, hatred, religious fundamentalism and political pesimissim. PRAs massively benefit respectful criticism over emotional and outrage-based criticism (including excessive sensitivity at satire). Criticism will always be a part of democracy, but it requires mutual respect between the two parties, as it can otherwise increase polarisation, tribalism and doesn’t lead to any constructive discussions. This does not mean that PRA would downrank provocative satire, as satire is important in democracy. PRAs should also favour professional journalism. PRAs also give a slight boost to positive sentiment (inspiration, joy, optimism, affection etc.) and good news to prevent doomscrolling and collective pessimism. Positive content can do wonders to people (such as videos showing humanity’s progress in the fight against climate change). When designing PRAs one however needs to be careful not to create a dictatorship of the smiley, where users only get recommended positive posts - as criticism is an important part of the democratic process, people should also see that sadness and failure is a part of life (in order to prevent the illusion of inadequacy) and the culture on social media should not encourage toxic positivity. However having a slight positive sentiment bias can have incredible effects on a society - it can improve consumer confidence, optimism and most imporantly it can inspire people to aim for new frontiers, learn new things and improve.

Conclusion#

In this short essay I hope to have presented the case to embrace technology to improve modern democracy by addressing the Social Media Algorithm Problem (SNAP) as brought to light by Yuval Noah Harari’s Nexus. In order to protect the democratic discussion online and prevent an incresing number of people to consume disinformation and polarising content, often spread with malicious intent and utilised by dictatorships to divide and conquer democracies I agree with Harari to ban bots, but also propose to use positive reinforcement algorithms (PRAs) to reinforce constructive sentiments online and prevent the attention economy from being dominated by destructive forces as well as to fix some of the issues that modern social media has created.

I believe that a bot ban is very much justified and that people should voluntarily consider using platforms which utilise PRAs, as the current algorithms used by social media distort the sentiment in a negative way and have lead to a global democratic backsliding since about 2010 - especially with the rise of AI, new dangers await humanity, but these are not insurmountable. We need to protect our privacy and be aware of the biases of algorithms - and use them to serve democracy. We have the choice

Sources#

- Harari, Yuval Noah. Nexus: A brief History of Information Networks from tge Stonge Age to AI. Fern Press, 2024.

- The Power of Stories, According to Yuval Noah Harari by Next Big Idea Club: https://nextbigideaclub.com/magazine/power-stories-according-yuval-noah-harari-bookbite/32488/ (2025.02.22)

- Penn University - Digital Shred: The TikTok Algorithm Knew My Sexuality Better Than I Did – Repeller: https://sites.psu.edu/digitalshred/2021/12/13/the-tiktok-algorithm-knew-my-sexuality-better-than-i-did-repeller/ (2025.02.22)

- Süddeutsche Zeitung: https://www.sueddeutsche.de/projekte/artikel/politik/russland-propaganda-desinformation-social-design-agency-ilja-gambaschidse-sofia-sacharowa-facebook-telegram-memes-karikaturen-putin-ukraine-krieg-in-der-ukraine-sda-e843184/?reduced=true (2025.02.22)

- Sameer Bajaj, Book notes on Nexus: https://sameerbajaj.com/nexus/ (2025.02.22)

- Durrie, Bouscaren, Iran claims that protestors of stringent hijab laws are in need of psychiatric help: https://www.npr.org/2024/11/29/nx-s1-5208117/iran-claims-that-protestors-of-stringent-hijab-laws-are-in-need-of-psychiatric-help (2025.02.28)

- Tabia T. PRama, Chhandak Bagchi et al: Political Biases on X before the 2025 German Federal Election https://www.ucd.ie/cs/news/politicalbiasonxbeforethe2025germanfederalelection/ (2025.02.28)

- Maria Ressa, The Guardian: Meta is ushering in a ‘world without facts’, says Nobel peace prize winner https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/jan/08/facebook-end-factchecking-nobel-peace-prize-winner-maria-ressa (2025.02.28)

- Peter Suciu, Forbes, Elon Musk Questioned Value of ‘Legacy Media’ https://www.forbes.com/sites/petersuciu/2023/10/04/elon-musk-questioned-value-of-legacy-media/ (2025.02.28)

- MDR, Alter, Bildung, Geschlecht: Wer wählte wen? https://www.mdr.de/nachrichten/deutschland/politik/bundestagswahl-wer-waehlte-wen-100.html (2025.02.05)